Successfully Managing Agricultural Credit Risk Regardless of Agricultural Market Conditions

by Nicholas Hatz, Assistant Vice President, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City–Omaha Branch, and Sandra Schumacher, Supervisory Examiner and Relationship Manager, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis–Helena Branch

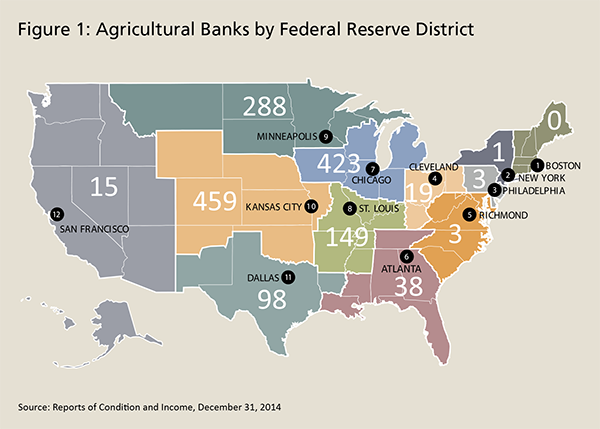

The roughly 1,500 agricultural banks1 in the United States play a crucial role in the U.S. financial system by helping meet rural producers' credit needs (Figure 1). Asset size comparisons with larger financial institutions understate agricultural banks' important contributions to both their regional economies and to the broader national economy. Market conditions in recent years, including volatile commodity prices, escalated farmland values in certain regions of the country, and rising farm production costs, have elevated the risks in agricultural lending, so much so that the Federal Reserve Board issued supervisory guidance in October 2011 on supervisory expectations for managing agricultural credit risk.2

This article provides a historical perspective on agriculture bank failures, discusses lessons learned about the increased risk in agricultural lending, and reviews aspects of the supervisory guidance on effective risk management policies. Since the Federal Reserve System supervises a large number of agricultural banks, its examiners have the opportunity to observe a wide range of risk management practices. Several proven risk management practices and some common mistakes observed during the examinations of these banks are also discussed. This analysis, however, is not all-inclusive.

Lessons Learned from a Past Farm Crisis and Common Mistakes

Agricultural markets deteriorated severely in the 1980s, affecting many agricultural banks. Although a significant number of agriculture banks failed in the 1980s, most survived.3 Those banks that weathered the crisis were characterized as having more conservative and consistent lending strategies, stronger risk management practices, and more formalized capital and strategic planning processes. In fact, the boards of the surviving banks had generally implemented strong risk management frameworks well in advance of adverse global market dynamics. Agricultural bank failures in the 1980s were largely a result of poor lending practices, including incomplete financial and cash flow analysis, overreliance on collateral values, poorly developed lending policies and procedures, poor documentation, and aggressive marketing to customers — with little concern for cash flow. Moreover, many borrowers were accustomed to obtaining credit with minimal financial documentation based on the anticipation that market prices and asset values would only continue to rise. Overall, one of the broad lessons learned from the 1980s farm crisis was that conservative and consistently applied risk management systems employed during both good and bad times enabled most agricultural banks to withstand even the most severe agricultural market downturns.

In looking back at the 1980s and the more recent financial crisis, it is apparent that several common factors contributed to the rise in problem banks. Among those factors were weak risk management practices and ineffective risk controls. Policies or procedures that described the bank's risk tolerance and provided the parameters for managing those risks were often lacking. There was often a slow response to identifying and downgrading problem loans because lending policies and risk management procedures were outdated, ineffective, or nonexistent. Inadequate training of less-experienced lenders often led to poor loan underwriting, loan structuring, and credit analysis.

With rapidly increasing real estate prices, many agricultural banks relied too heavily on collateral and misjudged farmland values. When conditions worsened, borrower equity positions and, ultimately, the value of collateral available to protect the bank against loss decreased significantly. Examiners often noted that credit decisions were based on collateral values instead of borrowers' debt service capacity. Weak underwriting can lead to problem loans and loan losses. At many failed banks, competitive pressures led to insufficient pricing for risk and relaxed underwriting standards. Loans were structured primarily to maintain business relationships and were based on management's previous experience with borrowers rather than on information in financial statements. Cash flow, revenue, and balance sheet forecasts were often unsubstantiated. Lending decisions based on insufficient credit analysis resulted in banks not understanding their borrowers' full financial condition. When market conditions deteriorated, borrowers were exposed to rising input costs and unstable prices, and the banks had no forewarning that the borrowers were facing debt repayment problems. The proper balance between managing credit risk and supporting a customer's needs is critical. A mismatch in amortization periods may strain cash flow and repayment ability, forcing the borrower to become noncompliant with the terms of the loan.

Supervisory Expectations for Effective Risk Management Practices

As outlined in Supervision and Regulation (SR) letter 11-14, a bank's risk management program should be commensurate with the size and complexity of the bank's exposure to the agricultural sector. As illustrated in Figure 2, SR letter 11-14 outlines six key risk management practices: assessment of creditworthiness, assessment of cash flow, underwriting standards, credit administration and controls, loan structure, and sound collateral margins and evaluations. Managing risk in these areas does not necessarily involve avoiding the risk; rather, it involves employing a consistent application of practices proven to control risk effectively within a wide range of outcomes.

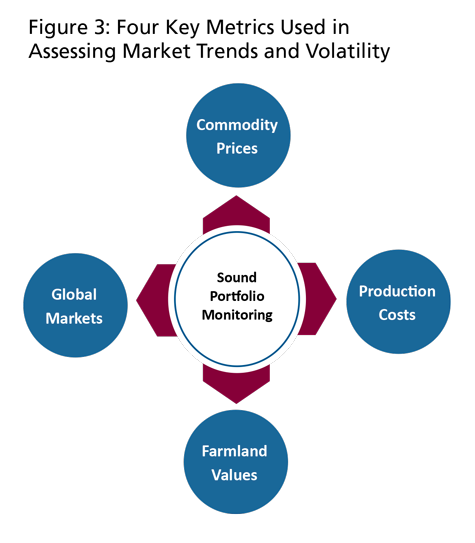

A sound risk management program includes a board of directors and management team that understand current issues, trends, and overall conditions in agricultural markets. Factors generally used to judge the strength of the farm economy, such as commodity prices, production costs, farmland values, and global markets, are illustrated in Figure 3. Accordingly, assessing emerging trends for each of these factors serves as a solid base to identify, measure, monitor, and control agricultural credit risks. Monitoring market factors and trends helps management and the board to identify sources of potential volatility and mitigate exposure to those various influences.

Source: SR letter 11-14, “Supervisory Expectations for Risk Management of Agricultural

Credit Risk,”

available at www.federalreserve.gov/bankinforeg/srletters/sr1114.htm

Assessment of Creditworthiness and Cash Flow

As outlined previously, prudent risk management practices are always relevant, regardless of agricultural market conditions. Insufficient credit analysis and inappropriate loan structure are often observed as precursors to a problem loan. In many cases, overreliance on collateral rather than cash flow as a source of repayment, generous loan terms toward favored customers, and inadequate real estate appraisals and evaluations are common underwriting pitfalls. Credit quality should take precedence over loan portfolio growth, and a bank should not allow the desire to build revenues to compromise credit standards. Safety of principal and assurance of repayment within agreed-upon terms should be at least as important as profiting from the transaction. A bank cannot charge a high enough interest rate to compensate for a loan that cannot be collected.

Source: SR letter 11-14, “Supervisory Expectations for Risk Management of Agricultural

Credit Risk,”

available at www.federalreserve.gov/bankinforeg/srletters/sr1114.htm

Another common mistake is that cash flow, revenue, and balance sheet forecasts are too often accepted at face value based on a borrower's assurances that the numbers are conservative. Such forecasts are assumptions, and the importance of verifying the assumptions' validity cannot be overstated. Consistent application of a cash flow sensitivity analysis is useful in determining an operation's ability to withstand risk and uncertainty. Financial analysis software, which is readily available and easy to use, may help banks assess a borrower's creditworthiness and analyze cash flow. Such software may provide a more thorough analysis of a borrower's repayment capacity and his or her ability to adapt to stressed conditions. Examiners have noted that many agricultural lenders have encouraged their borrowers to use these tools to better understand their own operations and financial conditions.

Underwriting Standards

Reliance on outdated or ineffective policies and procedures could possibly expose the bank to unnecessary risk. A significant number of policy exceptions can indicate that a bank is taking on additional risks and that underwriting standards are no longer in step with the current environment. It is important for banks to adhere to strong, well-developed policies and procedures in the current lending environment, where competition for quality borrowing relationships remains intense. Loosening loan underwriting criteria based on alleged offers from competition should be avoided. While lenders often state that exceptions were granted to meet competitive pressures, frequent contraventions of board-approved policy guidelines may cause examiners to question whether such loans should have been made.

A strong practice that examiners have observed during the recent upturn in land values is that many lenders have not used the current market asset valuations for land in lending decisions. Banks with strong credit risk management processes have been observed setting a dollar cap per acre, generally based on historical values, even though recent appraisals would support soaring land values. In this scenario, the borrower is required to provide upfront cash or equity and additional collateral to purchase the land and secure financing, thus creating a cushion if land values decline. By following this practice, these banks have maintained conservative underwriting standards, unlike many lenders in the early 1980s that allowed loan-to-value ratios for loans secured by farmland to exceed 80 percent based on the current, albeit inflated, market values.

Credit Administration and Controls

Clear guidelines should be in place to identify and correct problem loans. Delinquencies are often the first indication of problem loans and usually reflect deterioration in a borrower's financial condition, such as declining profits, decreasing sales, increased dependence on debt, and decreased working capital. Outdated financial statements are also an indication that the borrower may be experiencing financial problems, as the borrower may be reluctant to provide the bank with current financial information. Some aspects are out of the bank's and farmer's control, such as natural disasters (for example, flood, fire, hail, and crop or livestock disease); therefore, it is important for lenders to ensure sufficient insurance is in place to protect assets.

A bank should also have a policy that clearly indicates how carryover debt will be financed and monitored. There are no hard-and-fast rules on whether carryover debt should be adversely classified, but the decision should generally consider the borrower's overall financial condition and trends. In addition, to help identify any sudden material increase in the borrower's indebtedness or deterioration in performance, banks with strong credit risk management processes perform periodic credit bureau checks. Finally, examiners have found internal credit risk ratings to be effective when banks establish loan review programs to further assist in identifying problem loans. When examiners identify problem loans that were previously unknown to the bank, it generally reflects poorly on management's ability to identify and control credit risk.

By nature, a rural community bank's loan portfolio is often highly concentrated in agricultural lending. Recognition of the potential concentration risk in these banks' capital and strategic planning processes is particularly important. Regulators expect that management or the board will ensure that management information systems and monitoring procedures are formalized and consistently completed. Monitoring of concentration levels should be done on a granular level, meaning that the bank should measure more than a broad agriculture concentration. Banks are encouraged to have a loan portfolio diversification policy and set prudent exposure limits for agricultural loans by commodity type, geographic market, and individual borrowing relationship. Banks also benefit from concentration reports that are tracked in relation to capital at risk, rather than only tracking concentrations by the percentage of total loans.

Loan Structure and Sound Collateral Evaluations

Proper loan structure and terms are critical. Improper structure or terms could lead to inappropriately long amortization periods or even to lender liability issues in the event of a loan default. Furthermore, it is generally inappropriate to finance permanent working capital or other long-term needs using open lines of credit. Loans to fund noncurrent assets carry greater risk when repayment is generated by future cash flow. Instead, repayment terms should be linked to the primary source of repayment for the loan and the useful economic life of the assets being financed.

Structuring a loan to a borrower's business plans and cycles can ensure that payment schedules align with cash flows. For example, a crop operation set up to make monthly payments may have difficulty meeting payment obligations, since its cash flow is typically concentrated in the fall and winter months when the operation sells its grain after harvest. In this case, an annual payment schedule would be more closely aligned to the time when the borrower (in this case, the crop operation) receives income. However, annual repayment terms would likely be inappropriate for a dairy operator, which generally receives more regular weekly or monthly cash flows. Examiners have observed that many banks with strong credit risk management have appropriately structured weaker loans with an enhancement to support the credit (for example, an outside guarantee through the United States Department of Agriculture or Farm Services Administration).

Collateral evaluations should be well documented and performed at a frequency commensurate with the risk characteristics of the account. Frequent inventory reports, borrowing base certifications, and loan officer visitations are strong processes observed by examiners. For example, livestock operations that have regular turnover and values that fluctuate with the market price, such as feeder operations, require periodic counts and inventory monitoring to ensure that adequate collateral coverage and capital levels are maintained.

Conclusion

The potential always exists in the agricultural sector for reduced profitability and increased borrower stress based on the unknown and uncontrollable volatility in the marketplace. Historical hindsight provides examiners with the opportunity to analyze what has worked and what has not. Lessons learned from past economic downturns in the farm sector show that agricultural banks that pursued more conservative lending strategies and had stronger risk management practices with formalized capital and strategic planning processes were well positioned for both the up-and-down cycles of volatile agricultural markets.

Prompt identification of risks and appropriate management strategies to control risks are paramount to the success of every bank. Managing risks presents an additional challenge when a bank is dependent on a single sector of the economy — in this case, agriculture. Guiding banks through good and bad times requires proactive and diligent management oversight, as well as effective and informed board governance. It remains essential for the future prosperity of agricultural banking that banks implement prudent and consistent risk management strategies at all times, not only in stressed market conditions.

Agricultural Credit Risk Resources

The list below is not comprehensive; however, it includes important links to various available market data research.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago — AgLetter

www.chicagofed.org/publications/agletter/index

This quarterly publication summarizes survey data for agricultural land values and credit conditions in the Seventh District.- Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas — Agricultural Survey

www.dallasfed.org/research/agsurvey/

This survey reports on agricultural credit conditions and farmland values in the Eleventh District.- Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City — Survey of Tenth District Agricultural Credit Conditions

www.kc.frb.org/research/indicatorsdata/agcredit/#issue

This survey reports on agricultural credit conditions and farmland values in the Tenth District.- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis — Agricultural Credit Conditions Survey

www.minneapolisfed.org/publications/agricultural-creditconditions- survey

This survey reports on agricultural credit conditions and farmland values in the Ninth District.- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis — Agricultural Finance Monitor

http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/afm/

This quarterly survey reports on agricultural credit conditions in the Eighth District.- Federal Reserve Board’s Commercial Bank Examination Manual, Section 2140, “Agricultural Loans”

www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/supmanual/supervision_ cbem.htm- FedLinks: “Risk Management Supervisory Expectations for Agricultural Credit Risk,” November 2012

www.cbcfrs.org/fedlinks/2012/November2012.pdf

- Supervision and Regulation Letter 11-14 “Supervisory Expectations for Risk Management of Agricultural Credit Risk” www.federalreserve.gov/bankinforeg/srletters/sr1114.htm

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)

www.usda.gov

The USDA provides a wide range of reports and data on market conditions.

Back to top

- 1 Agricultural banks are defined as banks in which farm production and farm real estate loans equal 25 percent or more of total loans.

-

2

See Supervision and Regulation letter 11-14, “Supervisory Expectations for Risk Management of Agricultural Credit Risk,” available at

www.federalreserve.gov/bankinforeg/srletters/sr1114.htm.

-

3

See Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, “History of the Eighties — Lessons for the Future,” available at www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/history/.