The U.S. EMV Chip Card Migration: Considerations for Card Issuers

by Mary J. Hughes, Senior Payments Information Consultant, Payments Information and Outreach Office, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

The United States is the last developed country to migrate to Europay–MasterCard–Visa (EMV) integrated chip cards based on technology described in EMVCo’s1 proprietary global standard. The migration from magnetic stripe transactions is now underway, as the major U.S. card brands (Visa, MasterCard, Discover, and American Express) are encouraging retailers and issuers to move to chip-based transactions.

This article is intended to give community bankers an overview of what the EMV migration means for card issuers. It provides a brief explanation of the characteristics of chip technology and the impact that the EMV migration may have on U.S. payment fraud losses. It looks at the status of the migration in terms of both card issuance and merchant acceptance. The article concludes with a discussion of factors community banks should consider when deciding when and how to transition their card portfolios.

Characteristics of Chip Technology

“Chip” refers to the microprocessor embedded in credit, debit, and prepaid cards. Compared with a traditional magnetic stripe transaction, chip technology is designed to offer enhanced functionality in cardholder verification and transaction authorization. A chip card’s microprocessor stores information securely and performs cryptographic processing during payment transactions. If someone steals the static data in the magnetic stripe of a card, the thief can embed the stolen data in a different magnetic stripe, apply it to the back of another card, and use the counterfeit card to make purchases. Unlike the static data in a magnetic stripe transaction, a chip card transaction creates a dynamic code that is unique to that particular transaction, thus diminishing the value of stolen card data.

A chip is encoded with complex security credentials that make it difficult to counterfeit. This has resulted in lower fraud losses associated with card-present2 counterfeit cards in countries that have implemented EMV technology. For example, in the United Kingdom, there was a reduction of about 27 percent in card-present fraud after chip cards were implemented.3 Counterfeit card fraud represents almost half of the total global card fraud losses. U.S. card issuers and merchants are particularly hard hit, sharing card fraud losses of 12.75 cents out of every $100 in value spent.4

Although migrating to chip cards may produce important benefits, it may also result in unintended consequences, particularly for card-not-present (CNP) transactions. CNP refers to e-commerce transactions, mail order, or telephone sales in which the merchants are not able to inspect the cards. Chip card technology does nothing to protect CNP transactions. For example, several countries had a spike in CNP fraud5 when chip cards were introduced because fraud perpetrators turned their attention from card-present counterfeit fraud to the more vulnerable CNP channel. The experience in the U.S. will likely be the same. The 2013 Federal Reserve Payments Study found that CNP signature debit and credit card transactions are three times more likely to be unauthorized than card-present transactions.6 Issuers, merchants, card brands, cardholders, and others may consider implementing a variety of potential solutions7 to help mitigate or prevent CNP fraud. A discussion of these solutions is outside the scope of this article.

Status of the U.S. Migration to Chip Cards

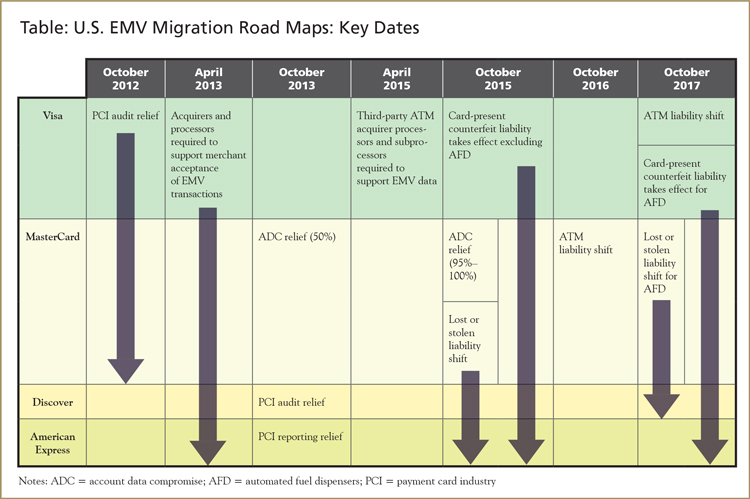

The four major card brands are leading the U.S. migration to chip cards in order to reap perceived benefits, including reduced counterfeit and lost or stolen card fraud, global interoperability of chip cards, and preparation for near field communication (NFC) mobile contactless payments. They have announced rule changes that are intended to spur EMV adoption. Their road maps (summarized in the table below) use a carrot-and-stick approach designed to accelerate adoption through merchant incentives such as Payment Card Industry Security Standards Council audit relief; upgrading of processing infrastructure to support EMV transactions; and fraud liability shifts8 affecting merchants, acquirers, ATM operators, and issuers.

Organizations that operate automated fuel dispensers (AFDs) have been granted extra time (until October 2017) to equip for chip card transactions because converting card readers at the pumps is complex and costly. For similar reasons, extra time is also being given to adapt ATM machines for chip card acceptance (until October 2016 for MasterCard and October 2017 for Visa).9

Forecasts vary, but it is estimated that about half of the 1.2 billion U.S. payment cards included EMV chips at the end of 2015, and most of them were credit cards.10 Several payment industry commentators have predicted that by 2020 more than 90 percent of U.S. cardholders will have an EMV card.

Debit card issuance has increased significantly since the beginning of 2015 now that debit routing challenges have been resolved. According to the 2015 Pulse Debit Study, 90 percent of the surveyed financial institutions said that they planned to start issuing EMV debit cards by the fourth quarter of 2015 and will complete their transition by the end of 2017. Natural migration based on a three- to four-year expiration cycle is the most popular strategy.11

Merchant acceptance of chip cards at point-of-sale terminals has been sluggish. The largest retailers are installing terminals capable of accepting EMV transactions. Smaller retailers are slower to equip for EMV acceptance, citing that upgrading terminals is not necessary or is too expensive or that they are not concerned about the fraud liability shift.12 One survey estimated that about 44 percent of U.S. merchants would be EMV ready by December 2015.13

A major incentive for merchants to become EMV capable is the shift in liability that took effect in October 2015. Previously, under the card brands’ operating rules, the issuer was liable for financial losses due to counterfeit card fraud. With the liability shift, a merchant will bear the loss if the issuer has issued chip cards to its cardholders and if that merchant has not been certified through its acquirer as being EMV compliant (by having implemented payment terminals that can read chip cards and taking other compliance steps).14 Also in October 2015, MasterCard, Discover, and American Express shifted the liability for a lost or stolen card to the party with the highest risk environment. Within that hierarchy, chip and PIN verification is considered more secure than chip and signature verification.

Issues and Decisions Facing Card Issuers

Community banks that issue credit, debit, or prepaid cards have either started migrating their card portfolios to chip cards or are (or will soon be) determining whether and when to adopt this technology. Making sound business decisions regarding this transition involves complex analysis.

As illustrated in the discussion in this section, a card issuer has many factors to assess before deciding whether to offer chip cards and, if so, how to implement the conversion. A significant consideration in the decision process is the impact of potential savings to an issuer resulting from the upcoming fraud liability shift on the card program’s profitability and cost structure.

Determine which cardholder segments should receive chip cards. Some issuers have decided to offer chip cards to selective segments, such as international travelers (both business and personal); new customers; or customers with lost, stolen, damaged, or expired cards. Retail data breaches that required issuance of new cards have also resulted in greater awareness of, confidence in, and demand for chip cards among U.S. cardholders because of perceived enhanced security features. Some issuers have opted to focus on credit cards first, with debit card migration planned at a later time. Other issuers have chosen to replace their entire portfolios with chip cards.

Take debit cards into consideration. U.S. issuers that decide to issue chip debit cards will likely want to preserve the routing choices available today. Moreover, these issuers must comply with Regulation II, which mandates that U.S. issuers offer merchants a choice between two unaffiliated networks when routing debit transactions. One solution is to instruct the chip manufacturer to place two application identifiers (AIDs) on the debit card chip, one for a card brand-specific AID15 (also referred to as a global AID) and another for the U.S. common debit AID. When a U.S. common debit AID is selected for a transaction, the acquirer can route the transaction to any network that the issuer has enabled for that card that supports that AID.

Decide which features to order on the chip itself when it is manufactured. The issuer may consider the following questions when deciding on which features to order:

- Should the chip be programmed with contactless16 or “dual interface”17 capability? Contactless-only cards will not qualify for liability shift protection for certain card brands, and some merchant terminals accept only contact EMV transactions.

- Will offline PINs (which are available only for contact transactions) and online PINs be enabled for credit cards?18 Debit card issuers will want to enable online PINs in order to offer PIN debit and ATM capability to their cardholders.

- What is the optimal memory size for the chip?

- What design features and branding options should be selected for the new cards?

Some service providers offer simplified, turn-key chip card solutions for issuers that prefer not to wrestle with all these choices. Chip cards typically have long shelf lives, so these decisions have lasting consequences.

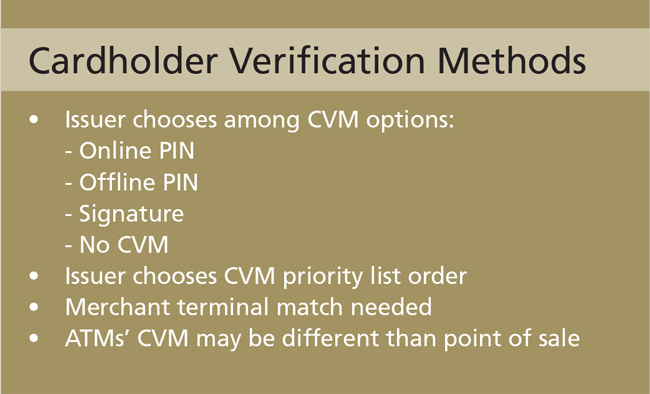

Select and prioritize cardholder verification methods (CVMs). Issuers generally specify cardholder verification methods and specify the hierarchy for merchants to follow on a particular transaction, as shown in the box.

To PIN or not to PIN? There is no mandate from the card brands regarding whether to use a signature or a PIN to verify that an individual is authorized to initiate a payment. Each issuing bank must decide whether it will issue a chip card as “chip and signature” or “chip and PIN.” Some issuers worry that cardholders will not use their cards if their PINs are required, believing that some Americans would rather sign their names than enter their PINs. The tradeoff is that “chip and signature” cardholder authentication is less secure than “chip and PIN” verification because “chip and signature” cards are generally more susceptible to lost or stolen card fraud. As noted earlier, some card brands are implementing a liability shift for lost or stolen fraud to incent adoption of PIN authorization.

Calculate costs and benefits. Issuers can expect to experience greater fixed and variable costs when implementing EMV cards, including costs associated with software, hardware, internal resources, and plastic. Chip cards are more expensive than magnetic stripe cards ($2 and more per chip card compared with a few cents for a magnetic stripe card). Issuers should weigh the cost of issuing cards against the financial impact of the fraud liability shifts by quantifying their current losses due to counterfeit and lost and stolen card fraud. They should also estimate lost revenue from cardholders who may demand chip cards and seek them elsewhere if their current issuers do not provide chip cards. Issuers should perform a comprehensive cost–benefit analysis to understand the business case associated with the move to chip cards.

Assess risk. Community banks should assess their risk tolerance in determining their response to the liability shift. Additionally, they should weigh the reputational risk of remaining with magnetic stripe cards in an environment prone to data breaches, given public perception that chip cards are more secure.

Schedule chip card migration with partners. The issuer has to coordinate the card migration with its card vendor, service bureau provider, transaction processor, core processing system provider, and card brand. Many other issuers may be attempting migration in the same tight time frame, so an issuer may face a queue and experience delays in obtaining its cards when wanted. Issuers should consider planning ahead and anticipate possible delays in the response time from the many service providers involved.

Provide training and education for staff and cardholders. Staff training is typically necessary to ensure customer inquiries are handled appropriately. Cardholder communication and education are also important to educate customers on how to use their new chip cards. Unlike magnetic stripe cards that are swiped, chip cards are inserted into a card reader and remain in the slot throughout the entire transaction. Savvy merchants wait to print a receipt until the card is removed so that the cardholder does not forget the card and leave it behind.

Card issuers should also consider the following questions:

- What does the future hold as far as adoption of mobile and contactless technology in payments? A Federal Reserve survey found that consumer adoption of mobile payments increased from 23 percent of smartphone users in 2011 to 28 percent in 2014.19 And how will chip technology integrate with mobile payments?

- Should investments be made in more advanced cardholder authentication and security methods? For example, biometric approaches20 strengthen cardholder authentication, and tokenization solutions21 devalue payment card data to fraudsters.

- What is the risk of delaying? Timing is another factor to consider. Migration to chip cards is a version of “musical chairs” for card issuers: No one wants to be the last one in a market to convert to chip cards because fraudsters tend to attack the easiest targets first. Because magnetic stripe cards are easier to counterfeit, they are generally attractive targets for thieves.

- When will most domestic merchants be equipped to accept chip-on-chip transactions at the point of sale so that cardholders can actually use their chip cards?

- How can the risks of CNP transactions be mitigated? Card issuers should consider exploring opportunities to address the increasing risk of CNP transactions as a result of EMV implementation, such as offering cardholders online PINs or one-day passwords or educating cardholders about the availability of tools such as e-mail alerts that flag CNP transactions.

What’s Next?

The migration of U.S. cards from magnetic stripe to chip technology, in terms of issuance of chip cards and merchant readiness to accept and process chip transactions, is expected to take some time for full acceptance by issuers, merchants, and cardholders. After more than two decades of chip cards based on the EMVCo standard, no country has achieved 100 percent issuance of chip cards or 100 percent acceptance of chip cards at the point of sale. It is expected that U.S. chip cards will continue to carry magnetic stripes for many years to come to ensure acceptance at merchants that are not EMV enabled.

Community bankers can prepare for the move to chip cards by learning more about the issues and arming themselves with facts to support informed business decisions. The cross-industry EMV Migration Forum’s website (www.emv-connection.com) has an excellent, informative Knowledge Center, and www.gochipcard.com is another website that provides useful information. Community bankers should seek out information from card brand representatives and card brand websites. Bankers can also rely on card manufacturers, core processing service providers, and other trusted partners to offer advice, estimate costs, evaluate risks, and help develop programs that are right for their financial institutions.

Back to top

- 1 EMVCo's owner members are Visa, MasterCard, UnionPay, American Express, JCB, and Discover.

- 2 Card-present refers to in-store transactions in which a card is physically present and available for inspection by the merchant.

- 3 Smart Card Alliance Payments Council, "Card-Not-Present Fraud: A Primer on Trends and Authentication Processes," White Paper, February 2014, available at http://ow.ly/Whq85.

- 4 "Card Fraud Losses Reach $16.31 Billion," The Nilson Report, Issue 1068, July 2015.

- 5 Douglas King, "Chip-and-PIN: Success and Challenges in Reducing Fraud," Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Working Paper, January 2012, available at www.frbatlanta.org/-/media/Documents/rprf/rprf_pubs/120111wp.pdf?la=en. Also see Mercator Advisory Group Research Brief, "EMV Adoption and Its Impact on Fraud Management Worldwide," January 2014, available at http://ow.ly/WhqQ7.

- 6 Federal Reserve System, 2013 Federal Reserve Payments Study, December 19, 2013, available at www.frbservices.org/files/communications/pdf/research/2013_payments_study_summary.pdf.

- 7 EMV Migration Forum, "Near-Term Solutions to Address the Growing Threat of Card-Not-Present Fraud," Card-Not-Present Fraud Working Committee White Paper, April 2015, available at http://ow.ly/Whre4. This white paper is an educational resource on best practices for authentication methods and fraud tools to secure the CNP channel as the U.S. migrates to chip technology.

- 8 EMV Migration Forum, "Understanding the 2015 U.S. Fraud Liability Shifts," White Paper, May 2015, available at http://ow.ly/WhrFK. This white paper highlights the fact that, in general, the party supporting the most secure technology for each fraud type will prevail in a chargeback, and in case of a technology tie, the fraud liability as of October 2015 generally is expected to remain as it is today - with the issuer.

- 9 For an informative look at the issues pertaining to ATMs and chip cards, see EMV Migration Forum, "Implementing EMV at the ATM: Requirements and Recommendations for the U.S. ATM Community - Version 2," June 2015, available at http://ow.ly/Whs0L.

- 10 See MasterCard, "More Than 575 Million U.S. Payment Cards to Feature Chip Security in 2015," August 13, 2014, available at http://ow.ly/Whs6a.

- 11 Oliver Wyman, "2015 Debit Issuer Study Executive Summary," Pulse, July 2015.

- 12 See the Wells Fargo/Gallup Small Business Index, July 2015, available at http://ow.ly/XhPCS.

- 13 The Strawhecker Group, "How Ready Are U.S. Merchants for EMV?," September 17, 2015, available at http://ow.ly/XhQhA.

- 14 The principle is that the party (issuer or merchant) that is the cause of a contact chip transaction not occurring (and thus falling back to a magnetic stripe transaction) will be financially liable for any resulting card-present counterfeit card losses.

- 15 Currently, Discover, MasterCard, and Visa provide U.S. common debit AIDs to be used on debit cards with their brands.

- 16 Contactless payment transactions (for example, using NFC) are popular in mass transit, parking, and ticketing applications.

- 17 Dual interface means an EMV card is set up for contactless and contact transactions.

- 18 With online PIN, the PIN is encrypted and verified online by the card issuer. When a chip card is manufactured, the offline PIN code is stored in the card's microprocessor. During an offline PIN cardholder verification, the PIN entered into the terminal or PIN pad is sent to the card. The card's microprocessor then returns one of two answers: (1) if the entered PIN matches the stored PIN, the card sends a confirmation signal to the terminal, and (2) if they are different, the card sends a failure signal. Offline transactions are used when terminals do not have connectivity (for example, at ticket kiosks) or in countries where telecommunications costs are high.

- 19 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, "Consumers and Mobile Financial Services 2015," March 2015, available at www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/consumers-and-mobile-financial-services-report-201503.pdf, page 5.

- 20 For example, biometric authentication techniques may rely on fingerprints and facial and voice recognition.

- 21 Tokenization replaces card data, such as the personal account number, with a surrogate value or "token" that has no value outside of a particular retailer or acceptance channel.